The fat pad was ignored for many years but has turned out to be critical in understanding anterior knee pain.

First published 2018, and reviewed August 2023 by Dr Sheila Strover (Clinical Editor)

First published 2018, and reviewed August 2023 by Dr Sheila Strover (Clinical Editor)

An alternative viewpoint on anterior knee pain - course

- CLINICAL CASES - Case 4

- CLINICAL CASES - Case 5

- BACKGROUND ANATOMY - Anterior compartment of the knee

- BACKGROUND ANATOMY - The Fat Pad

- BACKGROUND ANATOMY - The Infrapatellar Plica

- BACKGROUND ANATOMY - how the fat pad and infrapatellar plica form

- BACKGROUND PHYSIOLOGY - Kinematics of the knee

- BACKGROUND PHYSIOLOGY - Knee pain in general

- TAKEHOME MESSAGE - The surgical technique of Untethering the Fat Pad

The fat pad is a fibrous, sponge-like scaffold, fat-filled, and semi-liquid, so structured to be able to deform slowly when pressure is applied, regaining form quickly when pressure is removed. It is densely packed with nerves.

Its mechanical function is to be a space filler and hydraulic shock absorber. It has other functions including facilitating gliding and lubrication, protection of articular surfaces, an endrocrine role and finally a neurosensory and proprioceptive role.

The anatomy of the fat pad

Every human being is a unique creature. It follows from the above that the anatomic details of each knee are also unique. Many areas of the body store fat, and it follows that the amount of fat present in the fat pad is variable according to diet and genetic profile.

The reality is that there is almost infinite variation in the anatomy of the contents of the Anterior Compartment.

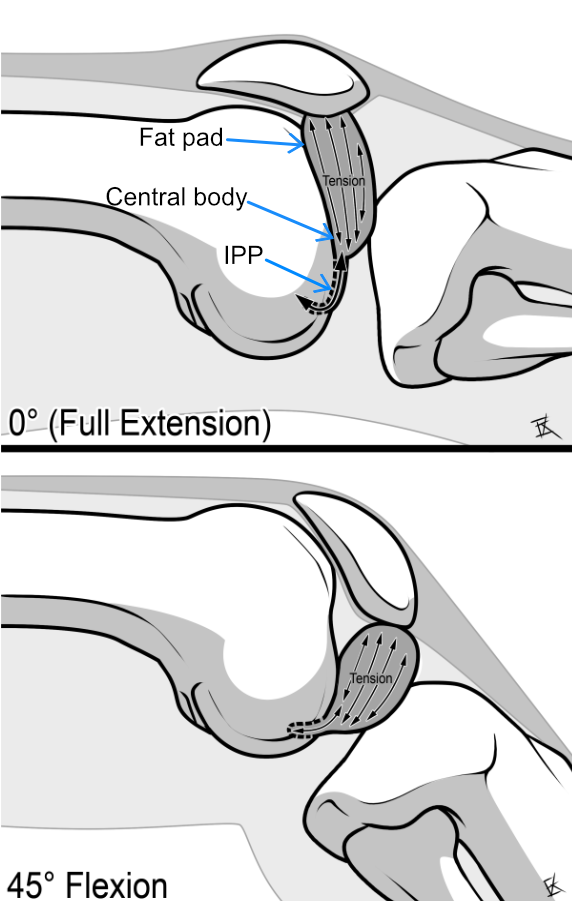

Take a look at how this unit behaves as the knee bends and straightens:

|

The illustration is of course a simplification - the outer attachment of the fat pad is the entire inner surface of the joint capsule and patellar tendon, and the deformity arises because the narrow central tether pulls the fat pad away from the wide base. You can appreciate this in the two dissections below.

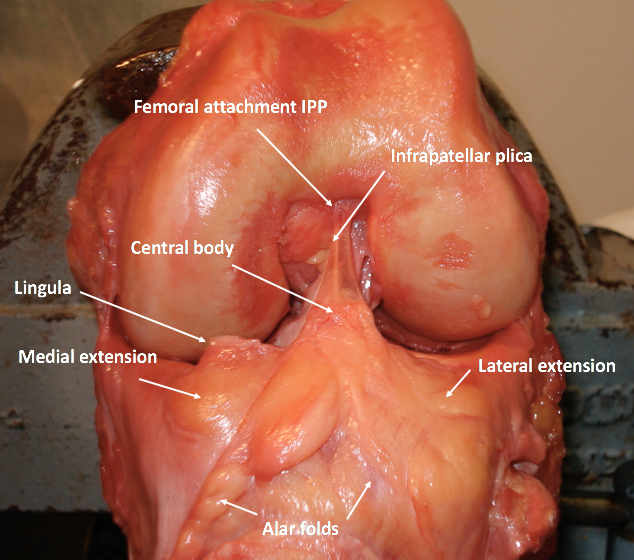

Next you see a dissection of a knee where the kneecap and its tendon have been separated from the muscle to which it is normally attached, and folded down so that we can see inside the anterior compartment.

|

Figure 3. This "opened up" view demonstrates the relationship of the IPP, central body, and fat pad with its alar folds and lingula. |

Shock absorption and Force Transmission

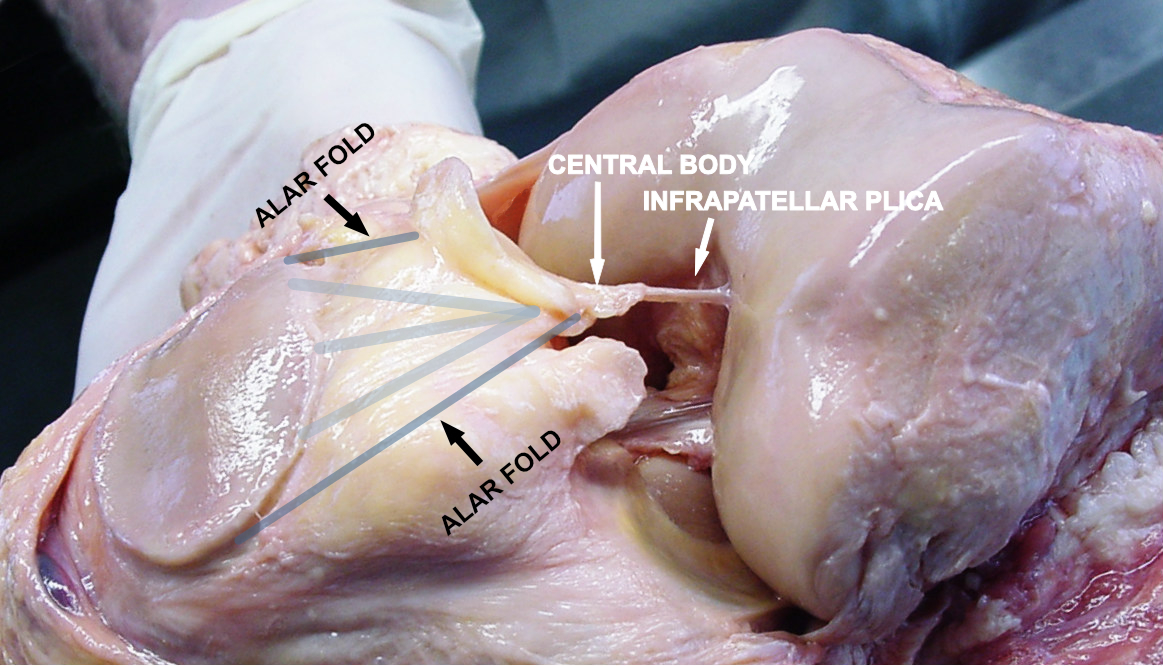

The entire capsule of the knee consists of a network of linked connective tissues, in which are key dense connective tissue connections that allow the forces within the knee to be transmitted appropriately as the limb moves. The alar folds radiating out from the fat pad form part of this force-transmitting network. In the next photograph (Figure 4) of a knee dissection, releasing the patella at its upper end and flipping the detached tissues down allows the important soft tissue relationships to be seen. Remember that the dense connective tissue network is usually hidden by the abundant fat. Force is transmitted along the dense connective tissue bands; the compressible fat, a natural shock absorber, is along for the ride, so to speak.

The relationship of the IPP with the fat pad

Here you can appreciate the infrapatellar plica (IPP), which in this person is a single, rope-like band of fibrous tissue attached to the fat pad by the conical central body. The dense connective tissue connections are marked in blue - I am highlighting them because they are the conduits for the contraction forces of the extensor muscles that perturb the fat pad and its contained array of nerves. This is a key concept to understanding the generation of Anterior Knee Pain (AKP).

Figure 4. Knee dissection showing the structures related to the fat pad.

References

1. Brooker B., Morris H., Brukner P., Mazen F., Bunn J. The macroscopic arthroscopic anatomy of the infrapatellar fat pad. Arthroscopy. 2009;25:839–845. [PubMed]

2. Gallagher J, Tierney P, Murray P, O'Brien M. The infrapatellar fat pad: anatomy and clinical correlations. Knee Surgery, Sports Traumatology, Arthroscopy. 2005 May;13(4):268-72.

PREVIOUS PART: BACKGROUND ANATOMY - Anterior compartment of the knee

NEXT PART: BACKGROUND ANATOMY - The Infrapatellar Plica