An ACL graft may fail if there is mechanical obstruction of the smooth passage of the graft in the notch of the femur. Dr Frank Noyes explains...

First published 2008, and reviewed August 2023 by Dr Sheila Strover (Clinical Editor)

First published 2008, and reviewed August 2023 by Dr Sheila Strover (Clinical Editor)

ACL reconstruction failure and revisions - course

- continued - "Most common causes of ACL graft failure"...

- ACL graft failure due to graft impingement

- ACL graft failure due to problems in graft tensioning and fixation

- ACL graft failure due to failure to address associated instabilities

- ACL graft failure due to inadequate rehabilitation programme

- Compounding problems that must be addressed in revision ACL surgery

- Graft options in revision ACL

- Contraindications to ACL revision

- What can one expect after ACL revision?

Graft impingement occurs when the graft becomes trapped in the notch between the rounded ends of the femur (intercondylar notch).

This can cause graft abrasion on the walls and edges of the notch, with wear and tear and eventual graft failure. The frayed edges can become bunched up and obstruct movement of the joint, causing decreased range of motion.

Usually, the surgeon can pre-empt this problem by careful attention to technique and performing a limited notchplasty and ensuring that adequate space exists upon completion of graft placement. In some cases, this problem may occur due to biological changes in the graft or the notch themselves.

|

|

| This left X-ray shows the joint where the ACL graft failed because the tunnels were too anterior. Take a look at the femur (top bone). The white bits are the fixation devices holding the graft in the tunnel. The right X-ray shows the original tunnel (yellow arrow) with the new tunnel behind it and in the correct position. You get an idea of how far anterior the original tunnel was made. If you cannot orientate, look for the patella bone - that is the anterior aspect. |

|

Causes of graft impingement

Causes of ACL graft impingement include -

Position of the femoral and tibial tunnels

Faulty operative technique is frequently a significant factor in failure of an ACL graft procedure, with misplaced femoral or tibial tunnels topping the list of causes of graft failure

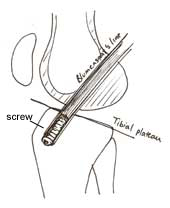

If an ACL graft is positioned too far anteriorly, then graft impingement may occur. If one looks at an X-ray with the knee in full extension, the tibial tunnel needs to open into the joint in a position that is behind (posterior) the junction two imaginary lines - one representing the tibial plateau and the other the roof of the intercondylar notch (Blumensaat's line).

If the opening of the tibial tunnel is in front of (anterior to) this line, the graft may be too tight in flexion and too loose in extension, and it is likely that the graft will impinge on the notch.

[Less commonly, the femoral tunnel may be positioned too posteriorly (towards the back). In this case, the fixation may fail due either to the posterior wall breaking apart and or to the graft being too tight in extension.]

The position of the tibial tunnel is also a cause for ACL graft failure, although poor positioning may cause chronic instability. If the tibial tunnel is too anterior, the graft may impinge on the notch of the femur and rupture, or the graft may be too tight in flexion. A graft which is placed too posteriorly in the tibia may in comparison be too lax in flexion.

Graft width and hypertrophy

Biologic graft material (allograft and autograft), when first harvested, is intrinsically weaker than the living ACL. The surgeon compensates by preparing the graft material so that its strength is adequate to provide stability until revascularisation and ligamentisation. This means that the harvested graft starts off with a greater circumference than the ligament it is replacing, and thus the notch space is already compromised from the beginning.

As revascularisation and ligamentisation occur, and new tissue cells grow into the graft, the graft may actually grow wider (hypertrophy) than it was at surgery. This may lead it to become impinged on the walls or roof of the notch.

Notch shape and size

There is wide variation in the size and shape of the notch in people who have not had any damage to the cruciate ligament. Females tend to have narrower intercondylar notches than males. There are also differences between races. There is some controversy about whether or not a narrow notch (notch stenosis) predisposes individuals to later cruciate damage. During the procedure of primary cruciate ligament surgery, most surgeons will widen the walls and the roof of the notch - a procedure known as notchplasty.

The need for routine notchplasty is controversial, and surgeons currently need to use their judgement in this respect, taking into account the width of the graft and the existing diameter of the notch.

Despite adequate notchplasty, graft impingement may still occur months after the initial reconstruction due to growth of fibrocartilage tissue from the edges of the notchplasty site. Hence, the surgeon needs to remain vigilant during the rehabilitation period and beyond, and it may prove necessary to repeat the notchplasty at a later date to prevent the graft from becoming compromised.

Cyclops lesion

A cyclops lesion is a lump of fibrous (scar) tissue that may develop within the notch of the femur, in relation to a damaged or reconstructed cruciate ligament, and can obstruct the knee from achieving full extension. It may arise from the old stump of the cruciate, or from drilling debris remaining in the tibial tunnel and, more rarely, from abraded graft fibres. If there is graft impingement, the scar tissue can result from repeated impingement on the notch with every knee extension.

PREVIOUS PART: ACL graft failure due to graft inadequacy

NEXT PART: ACL graft failure due to problems in graft tensioning and fixation